Political Empowerment of Women un the MENA Region

Introduction

Historically, women living in the MENA region were vulnerable to the discrimination and suppression of their basic human rights. Their involvement in political life of their countries was limited, while in some cases, they did not even have the right to participate in the political life. However, the situation has started to change in the late 20th – early 21st century, when the rise of globalization and wider spread of democracy in the world, along with the fast technological progress, have brought new feminist ideas to the MENA region. The revival of feminism and growing awareness of local women of their right to participate in the political life confronted historical and cultural barriers, since traditionally Arab society perceived women as second-class citizens. The Arab spring and profound democratic transformations that have started in many MENA countries contributed to the further progress of the feminist movement in the region[1]. More important, the wider and equal involvement of women into the political life of their countries became one of the main issues in the domestic politics. Many women striving for their right to take part in elections and be elected or simply to participate in the political life and political decision making process urged to reunite their efforts to push on their governments and legislators to create fair conditions for their involvement into the political life of their countries. Therefore, today, women steadily gain the ground in the political life of their countries in the MENA region, but they still have a long way to go to reach the truly equal position compared to men because they have to overcome socio-cultural biases, economic and political barriers.

The general low level of women political empowerment in the MENA region may be the result of certain cultural similarities between MENA countries, such as the prevalence of Islam, for example. However, there are obvious differences between MENA countries, where women may hold rom a third to zero seats in national parliaments of MENA countries. Such differences cannot explain the major difference between the political empowerment of women in the MENA region by religious or cultural background alone. Instead, there are likely to be other factors which may influence the disparity of the political empowerment of women in the region. In this regard, it is possible to suggest the hypothesis that the political empowerment of women in MENA countries may vary depending on the educational level of women, their involvement in the economic life of their countries and, what is probably the most important, the political regime, which may vary from democracy to the authoritarian or royal rule[2]. Hence, the higher educational level, the wider involvement of women in economic activities, and democratization of the political life of MENA countries are, in all probability, the major drivers of the political empowerment of women in those countries. However, education and economy alone are not determine the poor political empowerment of women in MENA countries now, because women have got much better economic and educational opportunities than they used to have in the past, while many countries have undergone democratic changes. Nevertheless, the political empowerment of women in the MENA region is still low that means that there is something else that bounds women emancipation and wider participation in the political life. In this regard, cultural norms and traditions play basically the main part in the failure of women to empower their political participation because the dominant culture is grounded on gender-related biases and views women as inferior to men, but recent economic, educational, and political changes lay the foundation for further cultural changes, which may put the end to women’s oppression in MENA countries, their full liberation and political empowerment.

The population of the MENA region

General characteristics

The prevalence of the young population is the distinct feature of the MENA region. The share of the young population varies from a quarter of the total population to almost a half (See App. Table 1. Demographics and Age of the MENA Population by Age Groups). Moreover, the economically active population comprises the majority of the population of MENA countries, with the older population comprising just a few per cents (3-8) at average (See App. Table 1). The presence of the young population implies that MENA countries have a considerable economic potential[3]. However, the question that begs is how these transformations will affect the position of women, who traditionally hold the inferior position in MENA countries. At any rate, their political empowerment is very weak, while their role in the economic life of their countries is secondary compared to the role of men.

The key demographic trends in the MENA region

The key trends in the development of the population of the MENA region include the growth of the literate population; large labor force; good economic opportunities for growth. These trends have a considerable impact on the socioeconomic development of the MENA region and affect social relations within MENA countries. The growth of the literate population creates conditions for the fast economic development of MENA countries, because education determines the qualification and professional development of individuals[4]. People with better education have better employment opportunities[5]. Illiterate population can count on low- or semi- qualified jobs only. In the contemporary economy, education is the major condition of the economic progress because education lays the foundation to the intellectual potential of nations, their technological and economic progress.

The large share of young and educated population creates conditions of the accelerated economic growth of MENA countries. In addition, the MENA region has a considerable potential in the labor force market because the young population comprises a large share of the total population of the region[6]. Therefore, countries of the MENA region have a large part of the economically active population, which can perform various jobs, conduct various business activities and, thus, contribute to the economic growth of their countries. The large share of the economically active population lays the foundation to the economic breakthrough of MENA countries, many of which suffer from the economic backwardness.

Therefore, MENA countries have good economic opportunities for the fast growth. The demographic situation is favorable for the economic development of MENA countries, but the presence of the young population is not the only factor that may boost their economies. Instead, there are also such factors as the level of education, which tends to grow and improve in MENA countries, and social stability[7]. The latter is the issue in the MENA region, especially in light of the Arab Spring, which involved serious of revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East. Also the civil conflict in Syria and emergence of ISIL/ISIS represent a serious threat to the further economic growth of MENA countries.

Nevertheless, they still have the potential and conditions for the considerable economic growth. What MENA countries really need is the elimination of social conflicts and intrinsic contradictions. This goal is possible to achieve through the elimination of inequalities between different social groups, including the inequality between men and women in their socioeconomic position and political participation. In this regard, gender inequality is one of the main issues because, on the one hand, women have already started to gain the political and economic ground in the MENA region, while, on the other hand, the resistance to the change of the role of women in MENA countries is still strong. Hence, numerous social conflicts and social tension in MENA countries persist.

Basic gender differences

Females hold a traditionally inferior position in society of the MENA region[8]. In fact, the culture of countries in the MENA region reveals that the male-dominated ideology prevails. The superiority of males in MENA cultures and societies is the result of several factors. First, males traditionally controlled the political and economic life in the region. Males also shaped the ideology, religious views, beliefs and philosophy of MENA countries[9]. This is why they exercise the full power in MENA countries, where women remained traditionally suppressed and doomed to play secondary parts in the life of MENA societies.

As males hold the dominant position in political, economic and social life, they set the full control over the life of people in the region. In fact, as males controlled political, economic and social life, females had no chance to challenge the position of males in those fields[10]. As a result, the MENA region witnessed the total domination of men, who ran countries and controlled virtually all spheres of social life. Instead, the role of women was doomed to focus on their households and families. Traditional female gender roles in the MENA region are often limited to household and family life. MENA cultures idealize women as good mothers and wives but not as civil rights activists or politicians. In such a context, men traditionally perform socially active role and turn out to be in the absolutely advantageous position compared to women.

Politics

Proportion of seat held by women in national parliament

One of the main indicators of the political empowerment of women is their representation in politics, namely their representation in parliaments. In this respect, women are, to a significant extent, under-represented in parliaments of MENA countries as Table 2 shows.

Table 2. Proportion of seats held by women in parliaments of MENA countries (1990-2015)

| 1990 | 2000 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| Morocco | 0.0 | 0.6 | 10.8 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 |

| Djibouti | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.7 |

| Jordan | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Turkey | 1.3 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 14.4 |

| Algeria | 2.4 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.6 |

| Tunisia | 4.3 | 11.5 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 27.6 | 27.6 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

| Bahrain | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Lebanon | 0.0 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Ethiopia | .. | 7.7 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 28.0 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 3.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 12.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | .. | .. | .. |

| Iraq | 10.8 | 7.6 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.3 | 26.5 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.4 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 1.5 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Israel | 6.7 | 12.5 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 24.2 |

| Kuwait | .. | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Sudan | .. | .. | 17.8 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 18.9 | 25.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.3 | 30.5 |

| Libya | .. | .. | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| Oman | .. | .. | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.0 | .. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 4.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Qatar | .. | .. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| West Bank and Gaza | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

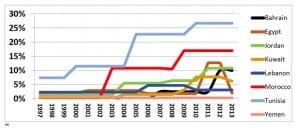

At the same time, it is possible to trace the trend to the growing share of women in parliaments of some countries in the MENA region, especially Sudan, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Israel and Iraq. The proportion of seats held by women in parliaments and governments of MENA countries is briefly presented in the graph below, which shows that the share of women in parliaments was relatively low, while their share in governments was even lower:

Fig.1 Seats held by women in parliaments of MENA countries (% of total number of seats)

In such a way, Fig. 1 shows the share of female legislators, senior officials and managers in governments of MENA countries, which varies but is clearly below the share of women in the total population of countries. By 2013, there is not a single country in the MENA region with the women involvement in legislative bodies or government that would exceed 30% of the total number of legislators or statespersons. Even though by 2015, there were changes introduced in legislation of some countries of the MENA region and changes in gender polices, like the provision of women with voting rights in Saudi Arabia, but such changes still fail to close gender gaps and women remain under-representing as they hold the minority of seats in their parliaments. At any rate, the share of seats held by women in parliaments of MENA countries is disproportional to their share in the total population of their countries.

Limited voting rights and opportunities

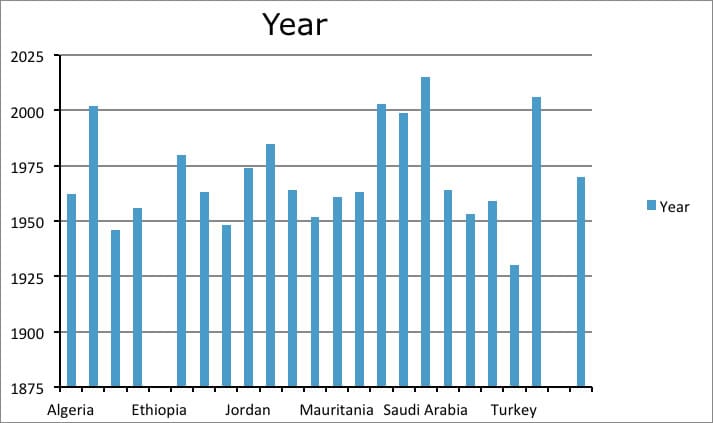

Another indicator of the political empowerment of women is their right to vote, which is definitely the fundamental right that gives women the access to vote. In this regard, women in the MENA region basically have the voting right, but, unlike western democracies, for example, some MENA countries granted their women the right to vote in the relatively near past[11]. In fact, it was Turkey that was the first to grant women with the voting right in 1930, while Saudi Arabia has granted women with the voting right just recently in 2015. In fact, the overwhelming majority of MENA countries did not grant women the voting right until the mid-20th century, while in some countries like Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and some others, women did not have the right to vote until the late 20th – early 21st century as Fig. 2 shows.

Fig 2. Female Right to Vote in MENA Countries

Therefore, women in MENA region were literally deprived of the possibility to take part in the political life of their countries until the mid-20th – early 21st century. Such policy was the result of the historical oppression of women and cultural traditions determined by the economic superiority of men in the past of MENA countries. In fact, men were breadwinners, while women were entirely dependent on men in MENA countries. Hence, men viewed women as second class citizens, who could not live independently without the support of men[12]. Consequently, if women were dependent on men, they could not take independent decision, especially in the field of politics. This is why legislators have preserved the voting right as the prerogative of men only. In addition, women were uneducated and often illiterate by the mid-20th century and even later in some MENA countries that was another reason why legislators preferred to prevent them from taking part in the political life and from granting them the right to vote.

Changes have started in the mid-20th century, when MENA countries have started to gain liberation from the colonial power of European countries, as was the case of North African countries and Palestine, for example. In some countries, like Egypt revolutions or coup d’état took place that involved some elements of democratization or granting citizens basic civil rights. Thus, profound socioeconomic and political changes and the desire of the population of MENA countries to reach the higher level of development and the higher standards of living made MENA countries following the lead of European nations and the US. They introduced the voting right as an essential element of progress but this was not only political or socioeconomic change but also an important cultural change. Policy makers of MENA countries have started to adopt basics of civil rights principles and they attempted to introduce principles of civil society to maintain the social stability in their countries.

The lack of the voting right means the consisting limitation of the political empowerment of women[13]. Hence, now they have neither experience nor political platform on the ground of which they could participate in the political life at the large scale. The participation in the political life is a new experience for them as well as for MENA societies since female politicians are very unusual for many citizens of MENA countries, including both men and women. This is why women often remain outsiders in the political life of MENA countries.

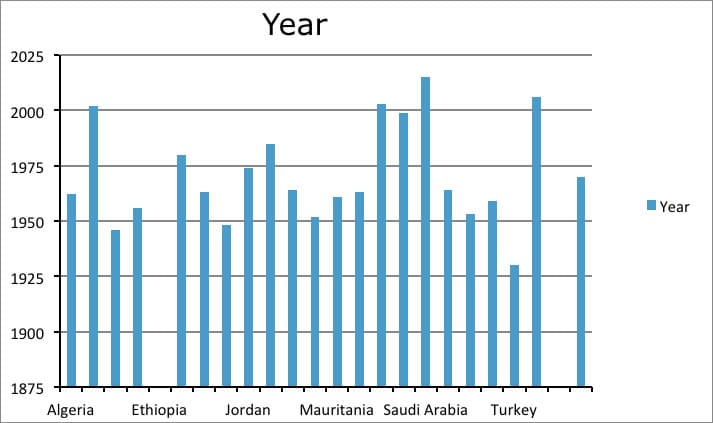

At the same time, granting women the right to vote still did not mean that they obtained absolutely equal rights and opportunities to participate in the political life. At this point, it is possible to refer to Fig.3 which shows age limitations for women to have the right to vote in the MENA region:

Fig. 3 Female right to vote age in MENA countries

Basically, they meet the general standard practice when voters get their right to vote at the age of 18-21, but some countries, like United Arab Emirates have raised the minimum age for women to obtain the right to vote up to 25. Such regulations do not prevent women from voting. However, a large share of women, who have basic human rights, or at least are supposed to have them, cannot vote and participate in the political life. Their participation in the political life is particularly important since a large share of the population in the MENA region is young people.

Limited involvement of women into political parties and elections

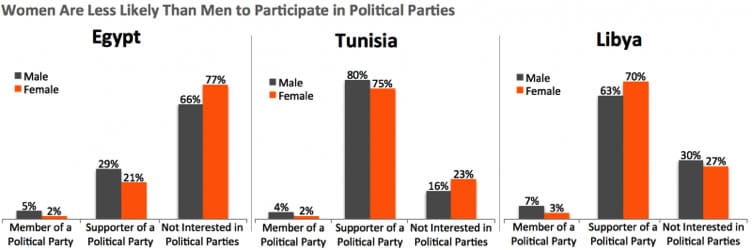

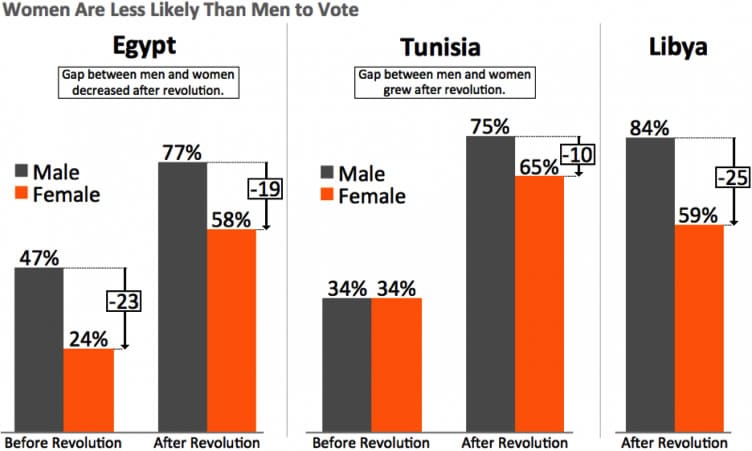

Women have a low level of their involvement into the political life of MENA countries. The involvement of women into political parties and elections as candidates clearly shows the minority position of women or their under-representation compared to men and to their share in the total population in their countries. For example, some countries of the MENA region have experienced revolutionary changes that have taken place recently, such as Tunisia, Egypt, Lybia, and some others[14]. The democratization was proclaimed as one of the major goals of those revolutionary changes. However, in spite of those revolutionary changes, the share of women in political parties and their involvement in elections is still consistently lower compared to men as Fig. 4 shows:

Figure 4. Participation of women in political parties in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya

Source: Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mei.edu/content/map/gender-gap-political-participation-north-africa

As a rule, women’s involvement into political parties is as less as twice compared to men. For example, 5% of men are members of political parties in Egypt and only 2% of women are members of political parties in Egypt. In Tunisia, the gap is lower but still there are just 2% of women and 4% of men, while the gap in Libya is similar to that in Egypt and comprises respectively 3% of women and 7% of men.

At the same time, researchers[15] distinguish regional differences in the level of political participation of women and their involvement in political parties. Researchers[16] point out that levels of political competition and participation of women in Yemen, Tunisia, and Algeria fit expectations about elections being safety valves or political spectacles, while Egypt’s presidential election stands apart, with exceptionally meager public involvement. In this regard, the major difference refers to cultural or civilizational changes that occurred to MENA countries and affected directly the political empowerment of women in those countries[17].

For example, Turkey was the first country of the MENA region that introduced the voting right for women but this was the result of the revolution and reforms conducted by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. These reforms have changed the country drastically. They aimed at the ‘Europeanization’ of Turkey that Turks viewed as modernization of the country and as an accelerated socioeconomic, political and cultural development[18]. The voting rights of women comprised an integral part of women and opened the way for the political empowerment of women in Turkey.

Similarly, the liberation of MENA countries, such as Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and others from European colonialism opened the way to their independent development but also urged them to conduct profound reforms. The colonial past of these countries contributed to the development of a deep sense of inferiority of MENA countries compared to European ones, which they viewed as more advanced. As a result, they tried to follow the lead of European countries in their socioeconomic and political development[19]. This why the sense of inferiority deep-rooted in MENA cultures after the colonial period encouraged countries to imitate European policies just like Turkey did in the 1920s – 1930 since they expected that westernization would bring them to prosperity[20]. Willingly or not, such westernization brought women of MENA countries the right to vote and contributed to their further political empowerment.

Women political participation and the Arab Spring

The participation of women in elections manifests different trends after the revolutions in North Africa. For example, the gap between female and male participation in election has decreased in Egypt, but increased in Tunisia after revolutions (See Fig. 5). At the same time, women in some countries have just got the voting right and the possibility to vote, which they did no really have in the past (See Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Participation of women in elections in Egypt, Tunisia and Libya

Source: Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mei.edu/content/map/gender-gap-political-participation-north-africa

However, the decrease of women participation is irrelevant because the total number of women participating in elections has increased. This was the case of not only Egypt, but also Tunisia, Libya and some other countries as the matter of fact. Moreover, even though the gap between men and women participation in elections persists but women tend to take more active part in the political life of their countries. For example, the gap between women and men participation into elections has dropped from -23% to -19% in Egypt, although it increased in Tunisia from 0% to -10% but then number of women participating in elections in both countries has almost doubled.

The lack of experience for women to participate in the political life, as both voters and candidates, influence their political behavior. The relatively recent introduction of their right to vote deprives them of the experience that may be essential for their effective involvement into elections and voting process. The behavior of women, who participate in elections, differs from that of men in terms of the decision-making process. To put it more precisely, women are more likely to take their decision to vote for the particular candidate till the day of elections that means that they take the decision in the last moment[21]. Also the decision taken by women often depends on their male guardian since often women in MENA countries vote for the same candidates as their spouses or other male guardians do.

The trend to take decision on the day of elections can make decisions taken by women rather emotional and spontaneous, while they have to make careful decisions to ensure their proper representation in the political life of their countries by their candidates. In actuality, women are still less likely to participate in the active political life and political parties than men[22]. Women still remain under-represented in political parties as well as parliaments of Arab countries, where revolutions have taken place recently.

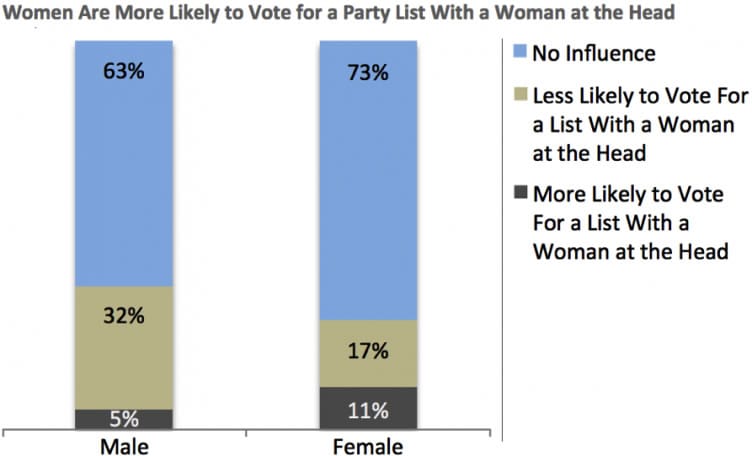

Researchers[23] reveal the fact that voters are rather indifferent whether women are enlisting at the top of party lists or not, while some voters have negative attitude to such parties. The likelihood of voting for a party list with a woman at the head varies depending on the gender but, as a rule, women at the head of their party lists have no effect on the majority of male and female voters. Nevertheless, about a third of male voters are unlikely to vote for parties with women at the head of their lists, while only a small portion of female voters is unlikely to support such parties.

Figure 6. Women enlistment into political parties in the MENA region

Source: Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mei.edu/content/map/gender-gap-political-participation-north-africa

Therefore, enlisting women at the top of political parties list does not grant political parties with any advantages in elections, but, on the contrary, such decision may have a negative impact on the overall success of such parties because they will likely to lose about a third of male voters and 17% of female voters. Such voter behavior discourages political parties from inclusion of women at their top list.

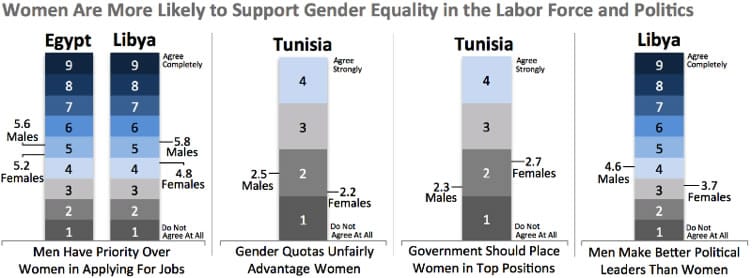

At the same time, women politicians stand for gender equality in the field of employment and government[24]. Such a stance is reasonable since it is the way to enhance the political empowerment of women in the MENA region. Fig. 8 reveals the attitude of women to their employment and participation in the government:

Figure 7. Attitude to women participation in employment and government

Source: Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mei.edu/content/map/gender-gap-political-participation-north-africa

The involvement of women into the government and legislative bodies is essential. Otherwise, they will not be able to stand for their interests. Men are likely to stand for their needs and interests. Consequently, they are likely to keep ignoring needs of women unless they face the pressure from the female electorate. In addition, parliament members or female professionals working in the government can stand for the wider political empowerment of women[25]. Hence, the wide employment of women in the government can help to empower women’s participation in the political life of MENA countries since women in parliament and government will stand for interests and needs of women.

Democratic revolutions as the major drivers of the empowerment of women

The analysis of consequences of Arab spring revolutions in regard to the empowerment of women and their participation in the political life of their countries, it is possible to trace a strong trend to the positive impact of revolutions or, to put it more precisely, democratic transformations on the empowerment of women and their wider participation in the political life as members of parliament as well as the average voters. At this point, it is possible to refer to the case of such countries as Tunisia and Iraq. Tunisia has experienced the revolution that was followed by the further democratization of the country, introduction of democratic elections and emergence of various political parties.

The case of Iraq reveals the impact of democratic transformations on the wider participation of women in the political life of the country. Under Saddam Hussein rule, women remained under-represented, whereas their involvement into the government or female members of parliament performed rather symbolic functions and did not really represent women in the political power of the country. Saddam Hussein held the full power over the nation and its political life. Political freedoms could not emerge and women remained suppressed and could not manifest their political preferences[26]. As a result, women could not have their representatives in the parliament or government, who could really stand for their interests. The overthrow of Saddam Hussein regime has opened the way for the rapid democratization of the country and the wider involvement of women in the political life. This is why the proportion of seats held by women in Iraqi parliament has skyrocketed from 7.6% in 2000 to 25.5% in 2006 and 26.5% in 2015 (See App. Table 6). Such a change is the obvious effect of the downfall of the authoritarian regime in Iraq.

At the same time, Arab Spring revolutions have brought the opposite effect on some countries. For example, Syria is still in the civil war and the political struggle between the authoritarian regime and opposition persists. Egypt has had the similar experience, but the insurgence of democracy was soon suppressed by el-Sisi, who has taken the power after the coup d’état. Hence, the suppression of democracy in Egypt resulted in the halt in the political empowerment of women in Egypt. The experience of Egypt proves the negative impact of authoritarian regimes on the political empowerment of women. In case of Syria, political freedoms are suppressed and women also suffer from the limited participation in the political life of the country.

The case of Iraq and Syria prove that the authoritarianism and suppression of women political empowerment. At the same time, they are not alone in their negative experience and the negative impact of the authoritarianism on the political empowerment of women. Iran is one of the most evident examples of the suppression of women political empowerment. The share of women in the parliament of Iran has not exceeded 4.1% within the last two decades. More important, the share of women in Iranian parliament has dropped from 4.1% in 2007 to 3.1% in 2015. In other words, the representation of women in Iranian parliament has dropped by a quarter in less than a decade, while countries, where the democratization has taken placed doubled or even tripled the representation of women in their parliaments as was the case of Iraq, for example.

At the same time, it is also possible to refer to the case of monarchies with the strict rule of monarchs in the MENA region. For example, Qatar and Yemen have virtually the lowest level of participation of women in politics and these countries have a strong royal rule with the consistent limitations of democracy. Qatar is a monarchy with the strong rule of the monarch, whereas Yemen is known as kletocracy, where the ruling class and officials, headed by the President Ali Abdullah Saleh, take advantage of corruption to extend their personal wealth and political power[27]. The corrupted regime of Yemen suppresses political freedoms and democracy as well as does the monarchy in Qatar. In such a situation, women remain under-represented in the national politics, whereas their involvement in the past was rather the result of the internal struggle within Yemen, when there were some manifestations of democracy and political rivalry in the late 1980s – 1990s. This is why by 1990, Yemen yet had 4.1% of women in the parliament. However, as the kleptocracy has grown in power, the share of women in the national parliament has dropped to zero.

Education

Many researchers[28] develop the idea that the political empowerment of women is, to a significant extent, restricted by their few educational opportunities. Literacy rate among the female population of the MENA region tends to grow (See App. Table 2 and Table 3). They reveal the correlation between literacy, higher education, economic and political opportunities. The traditional correlation between education, economy and politics implies that the education provides individuals with the educational basis on the ground of which they develop their political views and social consciousness. They become aware of the importance of the participation in the political life because it provides them with the opportunity to influence policies conducted by the government. In addition, education opens wider economic opportunities and people with higher education have better employment opportunities. Better employment opportunities enhance socioeconomic standing of individuals, while a significant socioeconomic position of individuals increases their impact on the political life of their country. Therefore, women potentially have an opportunity to empower their participation in the political life due to education.

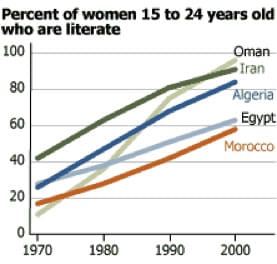

Literacy is one of the major indicators of the overall level of education in the country. Literacy among women in the MENA region grows and, at the moment, it is relatively high.

Literacy Rates Among Young Women in MENA region by countries, 1970-2000

Source: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics, “Literacy Statistics” (www.uis.unesco.org, accessed March 11, 2003).

The graph shows the considerable growth of the literacy rate since the late 20th century, mainly from the 1980s -1990s. Today, the literacy rate in many MENA countries is high, especially compared to the mid-20th century (See App. Table 3). This is why some researchers[29] claim that the political empowerment of women in MENA countries is still low, even though women are quite educated or literate, at the least.

However, it is impossible to make a definite conclusion that education does not matter in regard to the political empowerment of women in MENA region. At this point, the quality of education does matter that means that a literate woman has a very different educational background compared to the woman with a higher education and their worldview and political participation are likely to be different[30]. Today, the share of women with the higher education in the MENA region is quite low[31]. This is why the quality of education still may be a factor that deprives women in MENA countries from their political empowerment. Researchers[32] argue that women with the higher education are more likely to take part in the political life than illiterate women or women with the basic education.

In addition, women with the higher education are more likely to take an active part in the political life that means that they are more likely to participate in elections as candidates or to obtain appointments in the government[33]. Therefore, education and, to put it more precisely, the quality of education can encourage the political participation of women in the political life. At the moment, the quality of education of women in MENA countries is lower compared to men, at least, judging by the share of university graduates and degrees obtained by men and women in MENA countries (See App. Table 2).

Also women in MENA countries have got access to education just a decade or two ago or even more recently. Therefore, their education still does not have a large scale impact on their political empowerment because its impact is relatively new. For example, a female university graduate cannot become a President of Egypt or any other MENA country; neither can she normally in well-established democracies. Moreover, neither can male obtain a significant political position just after the graduation from the university. This is why it is possible to expect positive effects of education on the political empowerment of women in a long-run perspective.

Economy

In the past, the distinct feature of MENA economies was the little participation of women in economic activities. Women had a few job opportunities and dedicated their life to households and their families mainly, whereas economic activities were predominantly male domains. Women also confronted unsurpassable glass ceiling since they had no opportunity to obtain top positions in their organizations, government bodies, and other organizations. MENA cultural and socioeconomic norms did not admit women at managerial positions and, what is more, women were not even supposed to care about their professional education or career[34]. Hence, women were literally excluded from the economic life, but their exclusion from economic life limited their opportunities to take part in the political life of their countries because they had little economic impact in their countries and policy makers could simply ignore their position.

Today, the situation in the MENA region has changed for better for women, but there are still wide gaps between men and women in the field of economy. The wider participation of women in the economic life of MENA countries becomes one of the mainstream trends in the development of MENA economies. More than one in every eight private companies in the Middle East and Africa region is female-owned now[35]. In actuality, women have better education opportunity. In the contemporary economy, better education of women opens better employment opportunities for them. Therefore, women have managed to make a considerable progress in the improvement of their economic position. The improvement of their economic position increases the impact of women on the key socioeconomic processes.

However, many problems of the past persist. For example, the problem of glass ceiling is still the issue in the MENA region. Furthermore, women in MENA countries face employment discrimination and inequality. Women have fewer promotion opportunities and receive lower wages compared to men. The distinction between male and female jobs still persists. Hence, it is still impossible to close gender gaps in the field of economy and they are still large.

In actuality, the level of women’s engagement in the economy in MENA lags far behind the rest of the world. First, in terms of female labor force participation, 24 per cent of adult women in MENA – fewer than one in four women across all age groups – works or seeks paid work[36]. The figure for women in OECD countries is more than 60 per cent[37]. Second, among those labor force participants, 18 per cent were unemployed in MENA, compared to 6 per cent in the world as a whole, in 2010[38]. Consequently, the number of women in MENA who are actually in employment is even further behind in international terms: in MENA around 17.5 per cent of the adult female population, less than one in five women, are now employed, compared to nearly 50 per cent worldwide[39]. The data show that MENA countries are harboring a large underutilized pool of human skills and capabilities embodied in the ready supply of women’s labor and entrepreneurial ambition[40].

In such a situation, the question that begs is whether the persisting economic disparities between men and women that have been just mentioned above do matter in regard to the political empowerment of women in the MENA region or not. Many researchers are inclined to believe that the economic disparity does affect and prevent women from the political empowerment[41]. Politics mirrors, to a significant extent, the socioeconomic development. Economy contributes to the emergence of various interest groups. Therefore, the involvement of women into economic activities contributes to their growing involvement in and impact on those interest groups. These interest groups, in their turn, may and do have the impact on politics. For example, various interest groups in MENA countries sponsor political parties. If women play an important part in an interest group, than that interest group would support a political party that stands for interests and rights of women or that interest group may support the political part, which has a large share of women enlisted in its party list.

Social Life and Culture

Muslim norms and traditions are still very strong and maintain the women inferiority in political, economic and social life. The devaluation of women’s humanity, sexual harassment and other kinds of gender-based violence in the public and domestic spheres, inequality in family and personal status laws, and outdated religious discourses that see women as lacking in reason and inappropriate for ruling (justified by concepts such as ‘qiwaama’) continue to tremendously impact women’s capacity for meaningful and effective participation in political life[42].

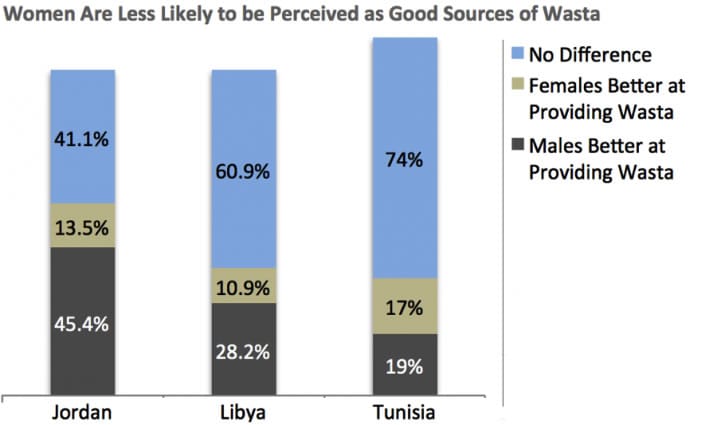

Women in Arab countries are less likely to be a good source of wasta (See Fig. 9), which means a sort of nepotism in North Africa and the Middle East[43]. The lack of wasta is rather a negative feature because wasta is essential for people living in MENA region to address burning issues, which they confront in their life, more effectively. Therefore, if politicians are poor in wasta, they are unlikely to gain the large scale public support. In this regard, female politicians turn out to be in a disadvantageous position compared to male politicians for voters in the MENA region.

Figure 8. Women and wasta in MENA countries

Source: Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mei.edu/content/map/gender-gap-political-participation-north-africa

Many women still prefer focusing on household than on their education, professional career or political activities. These cultural traditions are deep-rooted and women cannot always overcome[44]. In fact, women do not even try to overcome existing cultural barriers that prevent them from the participation in the political life because they take their inferior position and their focus on their households and family life for granted. They believe their lifestyle is right because it matches existing socio-cultural norms.

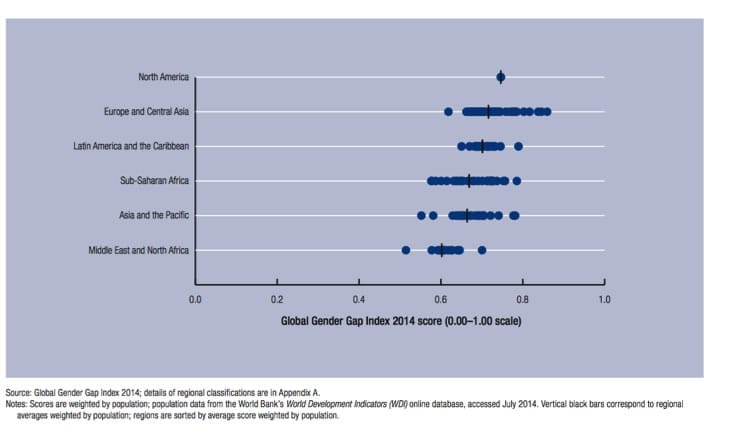

As a result, gender gaps in MENA countries persist and they are substantially higher compared to gender gaps in North America, Europe and even other Asian countries, where women also suffer from male-dominated culture oppression:

Figure 9. Global gender gaps and MENA countries

Nevertheless, feminist movements emerge in MENA countries as women become more educated and get wider economic opportunities to lead the independent life, regardless of the position of men. For example, in the past, women economically dependent on men and often they still are in MENA countries[45]. As a result, they developed cultural norms and traditions, which justified their inferior position and focus on their household and family life only. New educational and economic opportunities open the way for profound cultural changes that will liberate women in MENA countries from the oppression of male-dominated culture[46]. In such a way, women can break through cultural barriers and reach the consistent political empowerment.

The political consciousness of MENA women grows stronger as more and more women reach success in politics, obtain seats in parliaments and governments of MENA countries. In this regard, successes of women in economy or science are equally important because they create conditions for fundamental change of cultural biases and stereotypes which determine the inferiority of women’s position in MENA societies. Their successes prove that women can stand on the equal ground with men.

Countries with the high impact of religion on socioeconomic and political life have a fewer participation of women in the political life of the country. For example, Iran has low share of women holding seats in the parliament or government of Iran. Moreover, the domination of the religious ideology prevents women from the setting themselves free of gender-related biases because religion imposes traditional biases on women over and over again. Religious leaders continue to promote male-dominated ideology which virtually enslaved women and limited their life by household and family routine[47]. In such a situation, women have little options for the political empowerment because their cultural views and beliefs literally drag them down into the routine of their traditional lifestyle. Hence, even if women receive education, they will not change their worldview consistently, if this education is biased, as is the case of Iranian education, for example, because such education is grounded on strong religious beliefs, prejudices and gender-related biases.

Ways to the political empowerment of women in the MENA region

Changing the education style/material, making it more open for critical thinking and knowing the rights would be effective for changing the position of women in MENA countries. They could have become aware of the importance of their wider involvement into the political life of their country. What is more important, the change of the education style and content would raise the awareness of women as well as men that women have equal rights compared to men and there are no objective reasons to discriminate women in MENA countries by limiting their access to the political life. Changes in education will change the self-perception of women and raise their awareness as citizens that should have equal rights and opportunities compared to men, while there are no other objective reasons for the discrimination of women but cultural biases driven by the historical domination of men in economic, political and social life of MENA countries. Hence, the change of the education style and material would lead to change in culture and way of thinking.

However, one of the major challenges that women in MENA countries confront on their way to the active participation in the political life of their countries is the lack of support. Moreover, they often confront a severe opposition, which is very strong not only in their community or society but also within their own families. The lack of support from the part of family members is particularly challenging for women, especially in the context of cultural traditions of MENA countries, where families and family members play a very important part in the life of every individual, including not only women but also men. One of the main conditions of the active involvement of women in the political life of MENA countries is the support of family members to give more inspiration and motivation for women instead of categorizing them in one category. The family support could inspire women to take a proactive stand and start to take a more active part in the political part of their countries.

In fact, educational changes may lay the foundation to deeper cultural changes, which are essential for the political empowerment of women in the MENA region. Existing cultural norms and traditions still often discourage them from the participation in the political life, while many women believe that their votes and their participation in the political life do not matter at all[48]. If women grow up being aware of their equality compared to men and the importance of their involvement into the political life, they will change not only their behavioral patterns but they will also change their cultural values.

Cultural changes are essential for the political empowerment of women in MENA countries because cultural biases and stereotypes raise unsurpassable barriers on the way of women to politics. At this point, it is possible to refer to the concept of wasta once again, which is very important for MENA cultures. Today, people still believe that women do not have wasta that makes them inferior and incapable as politicians in a way compared to men. The lack of wasta means that women politicians cannot establish positive relations within the key stakeholders and they cannot resolve problems as successfully as male politicians can do. Cultural changes should bring the elimination of such biases, while the elimination of cultural biases is possible through new, bias-free education and enlightenment of the population of MENA countries.

Finally, there are differences between MENA countries but the general background of those countries is similar even with the current level of their openness. They have similar religion, culture, and economy that creates the common ground for their further development and the recommendations concerning the political empowerment of women given above may be applied successfully in those countries due to their common ground. The future political empowerment of women will need complex changes, but current changes in education and economy lay the foundation for the adequate inclusion of women into the political life, but cultural barriers remain quite high and they have to be finally eliminated to open the way to the full inclusion of women in the political life of MENA countries on the equal ground compared to men.

Conclusion

Thus, the political system and policies conducted in MENA countries are the major factors that affect the political empowerment of women in the region. The democratization and the introduction of democratic transformations brings positive effects even within former authoritarian states, like Tunisia, Iraq, or Morocco. In contrast, the maintenance or establishment of the authoritarian regime leads to the suppression of democratic liberties and the political empowerment of women, as is the case of Iran, Syria, Qatar, or Yemen.

In addition, the experience of women’s participation in elections and their voting rights are also important factors that determine their involvement into the political right of their countries. MENA countries have granted women since the mid-20th century mainly, while some countries like Saudi Arabia granted women with the voting right just in 2015. Hence, women have little experience of the participation in the political life that results in their under-representation and their weak position in parliaments and governments of their countries. Female voters also still have to gain the consciousness of the importance of their participation in elections and the political life and rise of their awareness of the impact on the political right of their countries, which the voting right gives them.

Furthermore, cultural biases and beliefs, such as the concept of wasta, which women in the MENA region are believed to lack of, also have a negative impact on their involvement into the political life of their countries. At any rate, the lack of wasta deprives women politicians and political parties they belong to of the support of a large part of the population, because voters believe that wasta, which female politicians lack, does matter.

The involvement of women in economic activities is also important. The increase of the economic role of women makes policy makers dependent on the support of women. Hence, women get an opportunity to influence policy makers by increasing their economic activities and economic role. Moreover, they can use their economy advancements as the ground to expand their impact on the national politics.

The wider inclusion of women into the government and government bodies and agencies can facilitate the political empowerment of women in MENA countries because women will show their capability to perform their job as legislators or statespersons well and they will stand for interests and needs of women, which male legislators and statespersons may by just unaware of.

Finally, women in MENA countries should be aware that there is no one, who can stand for their interests better than themselves. This means that women in the MENA region should enhance the feminist movement and take a proactive stand in regard to their participation in politics. They should focus on the enhancement of their political parties or their wider representation in political parties. They should try to become candidates to obtain seats in their national parliament or government. They should vote for political parties that make gender equality in politics, economy and other fields their priority.

References:

Bachelet, M. Reform to Reality Empowerment of Women in the Middle East. UN Women, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2011/6/reform-to-reality-empowerment-of-women-in-the-middle-east

Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mei.edu/content/map/gender-gap-political-participation-north-africa

Benstead, L. J., Amaney A. J., and Lust, E. (2015). “Is it Gender, Religion or Both? A Role Congruity Theory of Candidate Electability in Transitional Tunisia,” Perspectives on Politics, 13(1), 74-94.

Boughzala, M. and Hamdi, M. T. (2014) ‘Promoting Inclusive Growth in Arab Countries: Rural and Regional Development and Inequality in Tunisia’. Working Paper No.71. Global Economy and Development. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Charrad, M. M. (2011) ‘Gender in the Middle East: Islam, state, agency’, Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 417-437.

Charrad, M. M. (2012) ‘Family law reforms in the Arab world: Tunisia and Morocco’. Report for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Division for Social Policy and Development, Expert Group Meeting, New York, 15–17 May

Coris, C. (2013). “Working in a Hostile Environment: Female Labor Segregation and Women’s Impediments to Private Sector Opportunities in Jordan,” in Gender and Violence in Islamic Societies, edited by Zahia Smail Salhi. New York: I.B. Tauris.

Derichs, C. (2010). Diversity and Female Political Participation: Views on and from the Arab World. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

European Union (EU) (2010) ‘National Situation Report: Women’s Human Rights and Gender Equality’. Tunis: EGEP.

Eyben, R. (2011) ‘Supporting pathways of women’s empowerment A brief guide for international development organizations’. Pathways Policy Paper. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Hausmann, R., L.D. Tyson, and S. Zahidi, eds. (2012). The Global Gender Gap Report 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

Haghighat, E. (2013). “Social Status and Change: The Question of Access to Resources and Women’s Empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa,”

Journal of International Women’s Studies, 14, 273–299.

Labidi, L. (2007). ‘The Nature of Transnational Alliances in Women’s Associations in the Maghreb: The Case of AFTURD and ATFD in Tunisia’, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 3(1), 6-34

Lord, K. M. (2008). A new millennium of knowledge? The AHDR on building a knowledge society, five years on.Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Luttrell, C. et al. (2009). Understanding and operationalising empowerment. ODI Working Paper 308. November 2009. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Moghadam, V.M. (2003). Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, 2d ed. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Moghadam, V. and L.Senftova. (June 2005). “Measuring Women’s Empowerment: Participation and Rights in Civil, Political, Social, Economic, and Cultural Domains,” International Social Science Journal, 57, 389–412

O’Neil, T., Domingo, P. and Valters, C. (2014) ‘Progress on women’s empowerment: from technical fixes to political action’. Development Progress Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Ross, M.L. (2008). “Oil, Islam, and Women.” American Political Science Review, 102(1), 107-123.

Sanja, K. and J, Breslin. (2010). “Tunisia.” Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. Shavarini, M. (2006). “Wearing the Veil to College: The Paradox of Higher Education in the Lives of Iranian Women.”International Journal of Middle East Studies, 38, 189-211

UNDP. (2002). Arab Human Development Report, 53-54.

Worden, M. (2012). The Unfinished Revolution: Voices from the Global Fight for Women’s Rights. New York: Seven Stories Press.

World Bank. The Road Less Travelled; Education Reform in the Middle East and North Africa, MENA Development Report, Washington DC: World Bank, 2008.

World Bank, Jobs for Shared Prosperity: Time for Action in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2013.

World Bank, Opening Doors: Gender Equality and Development in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington DC: World Bank, 2013b.

World Bank/IFC, Women, Business and the Law. Removing Restrictions to Enhance Gender Equality, World Bank, Bloomsbury, 2014.

Zaatari, Z. No Democracy without Women’s Equality: Middle East and North Africa. Conflict Prevention and Peace Forum, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/4066249/No_Democracy_without_Women_s_Equality_Middle_East_and_North_Africa1

Appendix:

Table 1 Population of the MENA region

| Population millions | Average annual population growth % | Population age composition | Crude death rate 1,000 people | Crude birth rate 1,000 people | ||||||

| Age 0 —14 % | Age 15-64 % | Age 65+ % | ||||||||

| 2000 | 2014 | 2025 | 200014 | 201425 | 2014 | 2014 | 2014 | 2013 | 2013 | |

| Algeria 31.2 | 38,9 | 45,9 | 2 | 1 | 28 | 66 | 6 | 6 | 24 | |

| Bahrain 0.7 | 1,4 | 1,6 | 5 | 1 | 21 | 76 | 2 | 2 | 15 | |

| Djibouti 0.7 | 0,9 | 1,0 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 63 | 4 | 9 | 27 | |

| Egypt, Arab 68.3 | 89,6 | 108,9 | 2 | 2 | 33 | 62 | 5 | 6 | 23 | |

| Ethiopia 66.4 | 97,0 | 125,0 | 3 | 2 | 42 | 54 | 3 | 8 | 33 | |

| Iran, Islamic 65.9 | 78,1 | 86,5 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 72 | 5 | 5 | 19 | |

| Iraq 23.6 | 34,8 | 45,6 | 3 | 2 | 41 | 56 | 3 | 5 | 31 | |

| Israel 6.3 | 8,2 | 9,5 | 2 | 1 | 28 | 61 | 11 | 5 | 21 | |

| Jordan 4.8 | 6,6 | 7,5 | 2 | 1 | 36 | 60 | 4 | 4 | 27 | |

| Kuwait 1.9 | 3,8 | 4,7 | 5 | 2 | 22 | 76 | 2 | 3 | 21 | |

| Lebanon 3.2 | 4,5 | 4,5 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 68 | 8 | 4 | 13 | |

| Libya 5.3 | 6,3 | 7,1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 66 | 4 | 4 | 21 | |

| Morocco 29.0 | 33,9 | 38,3 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 67 | 6 | 6 | 23 | |

| Oman 2.2 | 4,2 | 5,1 | 5 | 2 | 21 | 76 | 3 | 3 | 21 | |

| Qatar 0.6 | 2,2 | 2,6 | 9 | 2 | 15 | 84 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |

| Saudi Arabia 21.4 | 30,9 | 36,8 | 3 | 2 | 29 | 68 | 3 | 3 | 19 | |

| Sudan 28.1 | 39,4 | 50,7 | 2 | 2 | 41 | 56 | 3 | 8 | 33 | |

| Syrian Arab 16.4 | 22,2 | 28,3 | 2 | 2 | 37 | 59 | 4 | 4 | 24 | |

| Tunisia 9.6 | 11,0 | 12,0 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 69 | 7 | 6 | 20 | |

| Turkey 63.2 | 75,9 | 83,5 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 67 | 7 | 6 | 17 | |

| United Arab 3.1 | 9,1 | 10,4 | 8 | 1 | 14 | 85 | 1 | 1 | 14 | |

| West Bank and 2.9 | 4,3 | 5,6 | 3 | 2 | 41 | 57 | 3 | 3 | 30 | |

| Yemen, Rep. 17.8 | 26,2 | 33,2 | 3 | 2 | 41 | 57 | 3 | 7 | 31 | |

| World 6,116.0 | 7 260,7 | 8 131,0 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 66 | 8 | 8 | 19 | |

Table 2 Gross enrollment ratio

| Gross enrollment ratio | Net enrollment rate | |||||||

| Preprimary % of relevant age group | Primary % of relevant age group | Secondary % of relevant age group | Tertiary % of relevant age group | Primary % of relevant age group | Secondary % of relevant age group | |||

| 2013 | 2013 | 2013 | 2013 | 1999 2013 | 1999 2013 | |||

| Algeria 79 | 119 | 98 | 33 | 86 97 | 51 .. | |||

| Bahrain 53 | .. | 101 | 40 | 96 .. | 87 93 | |||

| Djibouti 4 | 68 | 46 | 5 | 25 58 | 14 .. | |||

| Egypt, Arab 30 | 115 | 89 | 33 | 93 | 95 | .. | 85 | |

| Ethiopia .. | .. | .. | .. | 36 | .. | 11 | .. | |

| Iran, Islamic 38 | 119 | 86 | 58 | 86 | 98 | .. | 82 | |

| Iraq .. | .. | .. | .. | 89 | .. | 30 | .. | |

| Israel 112 | 104 | 102 | 67 | 97 | 97 | 96 | 98 | |

| Jordan 34 | 98 | 88 | 47 | 94 | 97 | 77 | 88 | |

| Kuwait .. | .. | .. | 28 | 93 | .. | 99 | .. | |

| Lebanon 102 | 113 | 75 | 48 | 97 | 93 | .. | 68 | |

| Libya .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | |

| Morocco 59 | 117 | 69 | 16 | 71 98 | .. 56 | |||

| Oman 52 | 113 | 91 | 28 | 83 94 | 65 83 | |||

| Qatar 58 | .. | 112 | 14 | 90 .. | 73 95 | |||

| Saudi Arabia 13 | 108 | 123 | 58 | .. 96 | .. 92 | |||

| Sudan | 38 | 70 | 41 | 17 | .. | 54 | .. | .. |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 6 | 74 | 48 | 31 | 94 | 62 | 39 | 44 |

| Tunisia | 40 | 110 | 91 | 34 | 96 | 99 | .. | .. |

| Turkey | ||||||||

| United Arab | 79 | 108 | .. | .. | 83 | 91 | 76 | .. |

| West Bank and 48 | 95 | 82 | 46 | 91 | 91 | 75 | 80 | |

| Yemen, Rep. 1 | 101 | 49 | 10 | 57 | 88 | 32 | 42 | |

| World 54 | 108 | 75 | 33 | 83 | 89 | 52 | 66 | |

Table 3

Literacy Ratio

| Primary completion rate Total Male Female % of relevant age group % of relevant age group % of relevant age group | Adult literacy rate | ||||||

| Male % ages 15 and older | Female % ages 15 and older | ||||||

| 1999 | 2013 | 1999 | 2013 | 1999 | 2013 | 200513 | 200513 |

| Algeria 80 | 106 | 81 | 106 | 78 | 105 | 81 | 64 |

| Bahrain 99 | .. | 100 | .. | 99 | .. | 96 | 92 |

| Djibouti 23 | 52 | 27 | 56 | 19 | 47 | .. | .. |

| Egypt, Arab 98 | 110 | 102 | 111 | 94 | 110 | 83 | 67 |

| Ethiopia 20 | .. | 26 | .. | 14 | .. | 49 | 29 |

| Iran, Islamic 93 | 104 | 95 | 103 | 90 | 105 | 89 | 78 |

| Iraq 57 | .. | 62 | .. | 51 | .. | 86 | 73 |

| Israel 104 | 102 | 105 | 102 | 104 | 103 | .. | .. |

| Jordan 98 | 93 | 97 | 94 | 99 | 92 | 98 | 97 |

| Kuwait 115 | .. | 115 | .. | 114 | .. | 96 | 94 |

| Lebanon 120 | 89 | 117 | 91 | 124 | 87 | 93 | 86 |

| Libya .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 96 | 84 |

| Morocco 55 | 99 | 61 | 99 | 48 | 98 | 76 | 58 |

| Oman 84 | 98 | 84 | 95 | 85 | 101 | 90 | 82 |

| Qatar 92 | .. | 87 | .. | 98 | .. | 98 | 97 |

| Saudi Arabia .. | 108 | .. | 104 | .. | 112 | 97 | 91 |

| Sudan .. | 57 | .. | 61 | .. | 53 | 82 | 66 |

| Syrian Arab 92 | 64 | 95 | 64 | 88 | 64 | 91 | 80 |

| Tunisia 91 | 98 | 91 | 97 | 90 | 98 | 98 | 96 |

| Turkey .. | 101 | .. | 102 | .. | 100 | 98 | 92 |

| United Arab 89 | 111 | 88 | 116 | 90 | 106 | 89 | 91 |

| West Bank 99 | 93 | 99 | 93 | 99 | 93 | 98 | 94 |

| Yemen, Rep. 56 | 70 | 76 | 78 | 34 | 62 | 83 | 52 |

| World 80 | 92 | 84 | 93 | 77 | 91 | 89 | 81 |

Table 4 Labor force participation rate

| Labor force participation rate | Labor force (ages 15 and older) | Labor force growth (%) | ||||||||||

| Male Female % ages 15 and older % ages 15 and older | Total Female millions % of labor force | |||||||||||

| 2000 | 2013 | 2000 | 2013 | 2000 | 2013 | 2013 | 200313 | |||||

| Algeria | 75 | 72 | 12 | 15 | 9,0 | 12,1 | 17,3 | 2,3 | ||||

| Bahrain | 86 | 87 | 35 | 39 | 0,3 | 0,7 | 19,5 | 7,4 | ||||

| Djibouti | 66 | 68 | 31 | 36 | 0,2 | 0,3 | 34,9 | 2,8 | ||||

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 73 | 75 | 19 | 24 | 20,1 | 29,0 | 24,1 | 2,8 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 90 | 89 | 73 | 78 | 29,0 | 45,4 | 47,3 | 3,4 | ||||

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 74 | 74 | 14 | 17 | 18,9 | 26,6 | 18,3 | 1,8 | ||||

| Iraq | 70 | 70 | 13 | 15 | 5,5 | 8,4 | 17,6 | 3,2 | ||||

| Israel | 61 | 69 | 48 | 58 | 2,5 | 3,7 | 46,8 | 3,4 | ||||

| Jordan | 69 | 67 | 13 | 16 | 1,2 | 1,7 | 18,2 | 2,8 | ||||

| Kuwait | 82 | 83 | 44 | 44 | 0,9 | 1,9 | 27,1 | 5,9 | ||||

| Lebanon | 71 | 71 | 19 | 23 | 1,0 | 1,6 | 24,1 | 3,0 | ||||

| Libya | 74 | 76 | 27 | 30 | 1,8 | 2,3 | 28,1 | 1,3 | ||||

| Morocco | 79 | 76 | 29 | 27 | 10,3 | 12,3 | 27,0 | 1,4 | ||||

| Oman | 78 | 83 | 23 | 29 | 0,8 | 2,0 | 14,1 | 8,6 | ||||

| Qatar | 92 | 96 | 38 | 51 | 0,3 | 1,6 | 13,1 | 13,8 | ||||

| Saudi Arabia | 74 | 78 | 16 | 20 | 6,5 | 11,8 | 15,2 | 4,5 | ||||

| Sudan | 75 | 76 | 29 | 31 | 8,2 | 12,1 | 29,4 | 2,9 | ||||

| Syrian Arab Republic | 81 | 73 | 20 | 14 | 4,9 | 6,0 | 15,4 | 1,6 | ||||

| Tunisia | 72 | 71 | 24 | 25 | 3,2 | 4,0 | 26,9 | 1,7 | ||||

| Turkey | 73 | 71 | 26 | 29 | 21,4 | 27,4 | 30,7 | 2,2 | ||||

| United Arab Emirates | 92 | 92 | 34 | 47 | 1,7 | 6,2 | 13,0 | 10,4 | ||||

| West Bank and Gaza | 65 | 66 | 11 | 15 | 0,6 | 1,0 | 18,5 | 4,2 | ||||

| Yemen, Rep. | 71 | 72 | 22 | 25 | 4,3 | 7,3 | 25,9 | 4,2 | ||||

| World | 79 | 77 | 52 | 50 | 2 773,5 | 3 337,3 | 39,6 | 1,4 | ||||

Table 5 Proportion of seats held by women in parliaments of MENA countries

| Female population % of total | Life expectancy at birth Male Female years years | Teenage mothers % of women ages 1519 | Unpaid family workers l Male Female % of male % of female employment employment | Female part time employment % of total | Female legislators, senior officials, and managers % of total | Women in parliaments % of total seats | % Change | ||||

| 2014 | 2013 | 2013 | 200713 | 2013 | 2013 | 200712 | 200813 | 1990 | 2015 | ||

| Algeria 49.7 | 69 | 73 | .. | 2,0 | 2,9 | .. | 11 | 2 | 32 | 30 | |

| Bahrain 37.9 | 76 | 77 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 8 | ||

| Djibouti 49.8 | 60 | 63 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 0 | 13 | 13 | |

| Egypt, Arab 49.5 | 69 | 74 | 10 | 5,5 | 34,9 | .. | 7 | 4 | .. | ||

| Ethiopia 50.1 | 62 | 65 | 12 | .. | .. | .. | 22 | .. | 28 | ||

| Iran, Islamic 49.6 | 72 | 76 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 13 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Iraq 49.4 | 66 | 73 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 11 | 27 | 16 | |

| Israel 50.5 | 80 | 84 | .. | 0,1 | 0,2 | 69 | 32 | 7 | 24 | 17 | |

| Jordan 48.7 | 72 | 76 | 5 | 0,4 | 0,3 | .. | .. | 0 | 12 | 12 | |

| Kuwait 43.8 | 73 | 76 | .. | 0,4 | 0,6 | .. | .. | .. | 2 | ||

| Lebanon 49.7 | 78 | 82 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Libya 49.6 | 73 | 77 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 16 | ||

| Morocco 50.6 | 69 | 73 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 13 | 0 | 17 | 17 | |

| Oman 34.2 | 75 | 79 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 1 | ||

| Qatar 26.8 | 78 | 79 | .. | 0,1 | 0,0 | .. | 12 | .. | 0 | ||

| Saudi Arabia 43.4 | 74 | 78 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 7 | 0 | 20 | ||

| Sudan 49.8 | 60 | 64 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 31 | ||

| Syrian Arab 49.4 | 72 | 78 | .. | 2,4 | 8,2 | 27 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 3 | |

| Tunisia 50.6 | 72 | 76 | .. | 3,2 | 8,0 | .. | .. | 4 | 31 | 27 | |

| Turkey 50.8 | 72 | 79 | .. | 4,5 | 31,4 | 60 | 10 | 1 | 14 | 13 | |

| United Arab 26.3 | 76 | 78 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 10 | 0 | 18 | 18 | |

| West Bank and 49.3 | 72 | 75 | .. | 4,8 | 20,9 | .. | 10 | .. | .. | ||

| Yemen, Rep. 49.5 | 62 | 64 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 5 | 4 | 0 | -4 | 13 |

| World 49.6 | 69 | 73 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 13 | 23 | 10 | |

Table 6 Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments

| 1990 | 2000 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| Morocco | 0.0 | 0.6 | 10.8 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 |

| Djibouti | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.7 |

| Jordan | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Turkey | 1.3 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 14.4 |

| Algeria | 2.4 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.6 |

| Tunisia | 4.3 | 11.5 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 22.8 | 27.6 | 27.6 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

| Bahrain | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Lebanon | 0.0 | 2.3 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Ethiopia | .. | 7.7 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 28.0 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 3.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 12.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | .. | .. | .. |

| Iraq | 10.8 | 7.6 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 25.5 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 25.3 | 26.5 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.4 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 1.5 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Israel | 6.7 | 12.5 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 24.2 |

| Kuwait | .. | 0.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Sudan | .. | .. | 17.8 | 18.1 | 18.1 | 18.9 | 25.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.3 | 30.5 |

| Libya | .. | .. | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| Oman | .. | .. | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.0 | .. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 |

| Yemen, Rep. | 4.1 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Qatar | .. | .. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| West Bank and Gaza | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

Table 7 Female legislators, senior officials and managers (% of total) in MENA countries

| 1990 | 2000 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Algeria | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 10.6 | .. | .. |

| Bahrain | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Djibouti | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Ethiopia | .. | .. | 15.7 | .. | .. | .. | .. | 19.9 | 22.1 | .. | .. | .. |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | .. | 10.1 | 10.8 | 11.1 | .. | .. | .. | 13.5 | 9.7 | 7.1 | .. | .. |

| Iraq | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | .. | .. | 14.6 | 13.3 | 13.3 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Israel | .. | 27.2 | 30.1 | 29.7 | 32.1 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Jordan | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Kuwait | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Libya | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Lebanon | .. | .. | .. | 8.4 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Morocco | .. | .. | 11.9 | 12.1 | 12.8 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Oman | .. | 9.3 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Qatar | .. | .. | 7.3 | 6.8 | .. | 4.4 | .. | .. | .. | 12.2 | .. | .. |

| Saudi Arabia | .. | .. | 8.9 | 9.2 | 7.1 | 5.4 | .. | .. | .. | 6.8 | .. | .. |

| Sudan | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Syrian Arab Republic | .. | .. | .. | 10.2 | .. | 8.3 | 9.2 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Tunisia | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Turkey | .. | .. | 8.2 | 8.6 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.0 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| United Arab Emirates | .. | 7.8 | .. | .. | 9.9 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| West Bank and Gaza | .. | 12.8 | 12.1 | 10.4 | 9.9 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

| Yemen, Rep. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 5.2 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. |

Table 8 Right to vote in MENA countries

| Year | Age | |

| Algeria | 1962 | 18 |

| Bahrain | 2002 | 18 |

| Djibouti | 1946 | 18 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 1956 | 18 |

| Ethopia | ||

| Iraq | full right 1980 | 18 |

| Iran, Islamic Rep. | 1963 | 15 |

| Israel | 1948 | |

| Jordan | 1974 | 20 |

| Kuwait | 1985 (removed then put back 2005) | 21 |

| Libya | 1964 | 18 |

| Lebanon | 1952 | 21 |

| Moritania | 1961 | |

| Morocco | 1963 | 21 |

| Oman | 1997 (full 2003) | 21 |

| Qatar | 1999 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 2015 | |

| Sudan | 1964 | |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 1949 (restrictions lifted 1953) | 18 |

| Tunisia | 1959 | 20 |

| Turkey | 1930 | 18 |

| United Arab Emirates | 2006 | 2006 |

| West Bank and Gaza | ||

| Yemen, Rep. | 1967 (full right 1970) | 18 |

[1] Charrad, M. M. (2011) ‘Gender in the Middle East: Islam, state, agency’, Annual Review of Sociology 37: 419

[2] Boughzala, M. and Hamdi, M. T. (2014) ‘Promoting Inclusive Growth in Arab Countries: Rural and Regional Development and Inequality in Tunisia’. Working Paper No.71. Global Economy and Development. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 45

[3] Haghighat, E. (2013). “Social Status and Change: The Question of Access to Resources and Women’s Empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa,” Journal of International Women’s Studies, 14, 277

[4] Moghadam, V. and L.Senftova. (June 2005). “Measuring Women’s Empowerment: Participation and Rights in Civil, Political, Social, Economic, and Cultural Domains,” International Social Science Journal, 57, 392

[5] Ross, M.R. (2008). “Oil, Islam and Women,” American Political Science Review, 102, 107–123

[6] O’Neil, T., Domingo, P. and Valters, C. (2014) ‘Progress on women’s empowerment: from technical fixes to political action’. Development Progress Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute, 184

[7] Haghighat, E. (2013). “Social Status and Change: The Question of Access to Resources and Women’s Empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa,” Journal of International Women’s Studies, 14, 276

[8] Moghadam, V. and L.Senftova. (June 2005). “Measuring Women’s Empowerment: Participation and Rights in Civil, Political, Social, Economic, and Cultural Domains,” International Social Science Journal, 57, 394

[9] Hausmann, R., L.D. Tyson, and S. Zahidi, eds. (2012). The Global Gender Gap Report 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, 22

[10] Haghighat, E. (2013). “Social Status and Change: The Question of Access to Resources and Women’s Empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa,” Journal of International Women’s Studies, 14, 278

[11] Eyben, R. (2011) ‘Supporting pathways of women’s empowerment A brief guide for international development organizations’. Pathways Policy Paper. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 42

[12] Luttrell, C. et al. (2009). Understanding and operationalising empowerment. ODI Working Paper 308. November 2009. London: Overseas Development Institute, 47

[13] European Union (EU) (2010) ‘National Situation Report: Women’s Human Rights and Gender Equality’. Tunis: EGEP, 38

[14] Eyben, R. (2011) ‘Supporting pathways of women’s empowerment A brief guide for international development organizations’. Pathways Policy Paper. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 34

[15] Sanja, K. and J, Breslin. (2010). “Tunisia.” Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 145

[16] Hausmann, R., L.D. Tyson, and S. Zahidi, eds. (2012). The Global Gender Gap Report 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, 27

[17] Moghadam, V.M. (2003). Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, 2d ed. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 135

[18] Ibid, 136

[19] Charrad, M. M. (2011) ‘Gender in the Middle East: Islam, state, agency’, Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 421

[20] O’Neil, T., Domingo, P. and Valters, C. (2014) ‘Progress on women’s empowerment: from technical fixes to political action’. Development Progress Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute

[21] Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015, 7

[22] Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015, 9

[23] Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015, 17

[24] Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015, 11

[25]Ross, Michael, L. 2008. “Oil, Islam, and Women.” American Political Science Review, 102(1), 111

[26] European Union (EU) (2010) ‘National Situation Report: Women’s Human Rights and Gender Equality’. Tunis: EGEP, 41

[27] Benstead, L. J., Amaney A. J., and Lust, E. (2015). “Is it Gender, Religion or Both? A Role Congruity Theory of Candidate Electability in Transitional Tunisia,” Perspectives on Politics, 13(1), 78.

10Shavarini, M. (2006). “Wearing the Veil to College: The Paradox of Higher Education in the Lives of Iranian Women.”International Journal of Middle East Studies, 38, 195

[29]Lord, K. M. (2008). A new millennium of knowledge? The AHDR on building a knowledge society, five years on.Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 154

[30] Moghadam, V.M. (2003). Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, 2d ed. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 174

[31] Derichs, C. (2010). Diversity and Female Political Participation: Views on and from the Arab World. Berlin: Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 135

[32] Moghadam, V.M. (2003). Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East, 2d ed. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers175

[33]Shavarini, M. (2006). “Wearing the Veil to College: The Paradox of Higher Education in the Lives of Iranian Women.”International Journal of Middle East Studies, 38, 198

[34]Shavarini, M. (2006). “Wearing the Veil to College: The Paradox of Higher Education in the Lives of Iranian Women.”International Journal of Middle East Studies, 38, 197

[35] Worden, M. (2012). The Unfinished Revolution: Voices from the Global Fight for Women’s Rights. New York: Seven Stories Press, 156

[36] World Bank, Jobs for Shared Prosperity: Time for Action in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2013, 15

[37] World Bank, Jobs for Shared Prosperity: Time for Action in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2013, 15

[38] World Bank, Opening Doors: Gender Equality and Development in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington DC: World Bank, 2013b, 11

[39] World Bank, Opening Doors: Gender Equality and Development in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington DC: World Bank, 2013b, 12

[40] World Bank/IFC, Women, Business and the Law. Removing Restrictions to Enhance Gender Equality, World Bank, Bloomsbury, 2014, 15

[41] Worden, M. (2012). The Unfinished Revolution: Voices from the Global Fight for Women’s Rights. New York: Seven Stories Press

[42] Zaatari, Z. No Democracy without Women’s Equality: Middle East and North Africa. Conflict Prevention and Peace Forum, 2015, 1

[43] Benstead, L.J. and Lust, E. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Middle East Institute, 2015, 14

[44] Labidi, L. (2007). ‘The Nature of Transnational Alliances in Women’s Associations in the Maghreb: The Case of AFTURD and ATFD in Tunisia’, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 3(1), 11

[45] Charrad, M. M. (2012) ‘Family law reforms in the Arab world: Tunisia and Morocco’. Report for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Division for Social Policy and Development, Expert Group Meeting, New York, 15–17 May, 154